Common misconceptions around gifted students and their teachers

The research is clear, but academics in the field of gifted education commonly report that misconceptions around our gifted population are still relatively widespread. Three commonly held misconceptions are shared in this paper, two that focus on the gifted student, and one that focuses on the classroom teacher. For purposes of definition, giftedness is defined here as those individuals who demonstrate an exceptional level of aptitude when compared to peers of a similar age (Gagne, 2009). Despite this general definition, there is significant heterogeneity within gifted populations (Wellisch, 2016).

Misconception #1: All gifted students are talented - The implications of using ‘giftedness’ and ‘talent’ interchangeably

“What is in a name?”

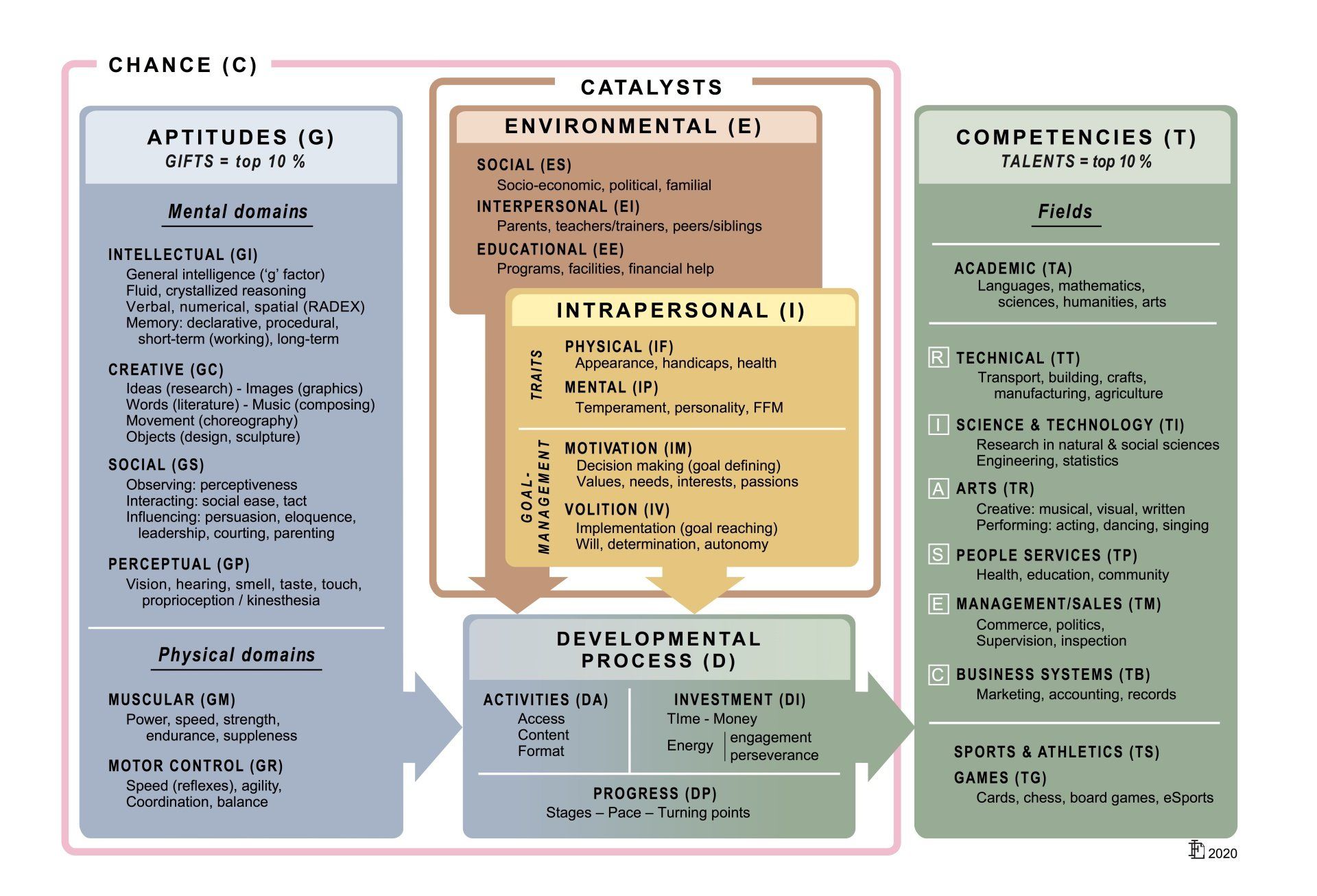

Whilst the lexicon used in the field of gifted education naturally, yet slowly, evolves, the terms of giftedness and talent are not synonyms although they are often used as such (Rimm, Siegle and Davis, 2018). Gagne’s Differentiated Model of Giftedness and Talent (DMGT) (2004; 2009) outlines a clear distinction between the two key concepts. Gifts are viewed as natural, untrained abilities that require development, while talents are defined as skills or capabilities that are learned and refined over time, leading to outstanding performance. If, in schools, we only identify talented individuals for gifted education provisions, we are potentially missing around 60% of gifted underachievers in school (Ronksley-Pavia & Neumann, 2020).

According to the DMGT (Gagne 2004 & 2009), to be gifted in a particular domain, an individual would fall within the top 10% of their same age peers. To be talented, on the other hand, requires performance or achievement in a particular field is in the top 10%, when compared with peers from that same field. It is vital that a distinction between the two terms be made to enhance professional understanding and aid the talent development process (Gagne, 2004). We risk gifted underachievers being overlooked if we choose only achievement in the talented range as the key indicator of giftedness. Underachieving gifted students come from the full socio-economic and cultural stratum, and also include those with disabilities that affect learning.

To develop talent, a series of supportive and timely influences, or catalysts (Gagne, 2009), need to be considered (Jung & Worrell, 2017). Catalysts (see Figure 1), fall into three key areas: intrapersonal, environmental and chance.

Quality programs and gifted education provisions can include some of the favourable catalysts. Without these gifted students may not develop their potential and thrive. Professional development is key to affording deeper understandings in schools (Rowan & Townend, 2016) as many gifted students will not thrive by themselves. This accounts for the high rate of underachievement in schools. It is these underachieving gifted students who are also at risk of social-emotional difficulties (Townend & Brown, 2016), and wellbeing is critical for healthy development in our students. Professional learning around identification across different populations of gifted students, including those who are underserved due to disadvantaged contexts for talent development, will give more students equitable opportunity to develop their potential.

Assumptions that gifted students will be high achievers and perform with excellence within talented fields is a common misconception. Giftedness and talent are not synonyms, and gifted students remain unidentified and unsupported across many educational contexts. The opportunity to learn about the process of transforming gifts into talents will remain elusive for many without opportunities for knowledge sharing and education, around the heterogeneous nature of our gifted students.

Misconception #2: Gifted students cannot have a disability

“If you have met one gifted learner with disability, you have met ONE gifted learner with disability”

Significant misconceptions and confusion surround gifted students who also have a disability that impacts learning (Townend & Pendergast, 2015). These students are also known as gifted learners with disability (GLD) or twice-exceptional students (2e). Commonly reported is the ‘masking effect’, in that the giftedness hides the disability or vice versa, further exacerbating the claim that these students are the most overlooked students in schools globally (Foley Nicpon et al., 2013).

In many cases, the giftedness of these students may be overshadowed by their learning needs or disability, and teachers require greater education and training to meet their unique needs (Norris & Dixon, 2011; Jung et al, 2022). The disability may present unique cognitive, social and emotional challenges which make identification of giftedness difficult (Townend & Brown, 2016). There is significant heterogeneity amongst GLD students as their characteristics of giftedness vary, but also do the characteristics of the disability.

GLD students may have one or more disability diagnoses such as Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Autism, Specific Learning Disorder (reading, written expression, or mathematics), physical disabilities and mental health needs (Nicpon Foley et. al, 2011; Townend & Brown, 2016). The apparent diverse nature of giftedness and the paradoxical features of disabilities can make educational adjustments appear complex and problematic (Assouline & Whiteman, 2011).

Empowering educators and informing them of how to identify and enable the giftedness, and to support the disability is key (Assouline & Whiteman, 2011). Careful collaboration with parents to ensure social and emotional wellbeing is crucial (Rowan & Townend, 2016). Professional learning and knowledge sharing for educators and their communities are very supportive in the identification and support of GLD learners because highly accessible strategies can be implemented to support them (Rowan & Townend, 2016). Even short one-day courses offered by universities can make powerful inroads around understanding of and provisioning for GLD students.

Misconception #3: Teachers are trained so why can’t they support my gifted child?

Are our teachers being asked to do more with less? ( Lucas and Frazier, 2014)

Gifted students, including GLD students, are consistently identified as being at risk of educational alienation, disengagement and underachievement (Rowan & Townend, 2016). In an increasingly crisis-rich education system that is poor in resources and time, our teachers require more support than ever to offer focused and strategic support for their gifted and GLD students (Rowan & Townend, 2016). Anecdotally, parents and carers report feeling consistently frustrated by an education system that either does not appear to understand or does not appear to sufficiently follow through with plans for gifted students.

Research suggests that many teachers believe that they do not have the necessary expertise to adequately support and extend their gifted students (Rowan & Townend, 2016) and this may be one of the causes of so many students being overlooked in the first misconception presented. With increasing awareness of the diverse needs of students across cognitive, psychosocial, motor, cultural, linguistic and communicative domains, the requirements for educators to support diversity in the classroom have become increasingly demanding (Coleman & Gallagher, 2015). It is generally accepted that teachers have a major impact on the educational achievements and psychological well being of our students (Townend & Brown, 2016) and, in our increasingly diverse classrooms which also include diverse abilities, teachers are naturally experiencing challenges when responding to the array of needs of their students (Rowan & Townend, 2016). As mentioned prior, as many as 60% of gifted students are not achieving to their potential (Siegle et al., 2014; Ronksley Pavia & Newmann, 2020) and many gifted students function at lower than 50% of their academic capability (Cross, 2013). These sobering figures have been partially attributed to teacher decision-making and their knowledge (or lack thereof) of differentiation and other appropriate instructional techniques (Rowan & Townend, 2016).

Research indicates that teachers are the most important school-based influence in determining student achievement. It is vital that all teachers in Australia, both pre-service and in-service, acquire the appropriate knowledge and skills to fully support our gifted students. The reality is that a vast number of our teachers do not feel well-prepared or trained to provide the specialist support that many students on the margins consistently require (Navarro et al., 2016). Although we have many wonderful specialist teachers who support our classroom teachers, they often must focus on many students across several classes and year groups. Accordingly, the principal in-class support is left to our mainstream educators, and this can leave them feeling that they are not adequately resourced to provide equitable educational opportunities (Navarro et al., 2016).

In an Australian Research Grant Project, the preparedness of early-career teachers to cater for diversity, including the needs of gifted students, was explored (Rowan & Townend, 2016). The findings were clear and responses from nearly 1000 early-career teachers indicated that less than half felt prepared to support diverse needs, including those of gifted and GLD students. They felt underprepared to support both the diversity and also to communicate sensitively with parents and carers, something that might underpin the 60% of those unidentified who underachieve at school.

It is little wonder then that we continue to have a high global attrition rate with our school educators (Geiger & Pivovarova, 2018). So why is it that our teachers feel so unprepared to work with our gifted students? Although this is a global phenomenon, the Australian context will be the focus here. The underpinning and often unexpected reason is teacher education for gifted students.

It has long been argued that a teacher’s lack of knowledge about an area will lead to low self-confidence and self-efficacy (Lemon & Garvis, 2015). This is no less relevant to gifted education where the research suggests that teachers’ low self-efficacy in this area is characterised by misunderstanding and fear (Geake & Gross, 2008). It has been shown that adequate initial teacher education and/or ongoing professional development have a direct impact on the classroom practices that lead to understanding and support for gifted students (Jung, 2014). Through high-quality training, that is evidence-based and led by gifted education experts, teachers can build their knowledge of gifted students’ learning needs, and this can positively influence their attitudes towards gifted education (Kronberg, 2018).

Why are teachers not receiving professional learning opportunities around gifted and GLD education? It is important to note that, at the point of writing, there are only two of the 43 universities in Australia that, as part of the initial teacher education degree, mandate a course in gifted education. Secondly, once teachers feel prepared for professional development, such as short 2-day courses, typical barriers can be a lack of resources or a rejoinder that there are ‘more pressing considerations’ that overshadow teachers’ opportunities.

However, the outlook is not bleak, at least from the perspective of UNSW, as more teachers and schools are electing to enrol in gifted education courses than ever before. In discussion with academics in this field around Australia, enquiries about professional development or ad hoc information sessions appear to be growing. When we work with people who appear frustrated by the lack of understanding in the system, it is important to understand that there are many barriers despite the colossal will of educators to understand and cater for all their students, including their gifted students.

It will take time, but the momentum will increase and, in the meantime, university academics in the field of gifted education continue to offer practical support and advice for those educators navigating the complex diversity of their classrooms.

Takeaway message

The considerable heterogeneity of gifted students alongside the diversity of their educational needs require ongoing professional development to drive wider understanding and support for their learning. It has been well documented that the needs of gifted students are not being met, and this stems from identification processes which need to be more inclusive of a range of student backgrounds and diversity, including gifted students who have concurrent disability. Greater focus on pre-service teacher education and in-service professional development is critical for supporting the optimal educational outcomes of gifted children.

References

Assouline, S., & Whiteman, C. (2011). Twice-exceptionality: implications for school psychologists in the post-IDEA 2004 era. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 27(4), 380-402.

Chaffey, G. W., Bailey, S. B., & Vine, K.W. (2015). Identifying high academic potential in Australian Aboriginal children using dynamic testing. Australasian Journal of Gifted Education, 24(2), 24-37.

Coleman, M. R., & Gallagher, S. (2015). Meeting the needs of students with 2e: It takes a team. Gifted Child Today, 38(4), 252-254.

Foley Nicpon, M., Assouline, S. G., & Colangelo, N. (2013). Twice-exceptional learners: Who needs to know what? Gifted Child Quarterly, 57, 169–180. doi:10.1177/0016986213490021.

Frazier, B., & Lucas, D. (2014). The Effects of a Service-Learning Introductory Diversity Course on Pre-Service Teachers’ Attitudes Toward Teaching Diverse Student Populations. Academy of Educational Leadership Journal, 18(2), 91-124.

Gagné, Françoys. (2004). Transforming gifts into talents: the DMGT as a developmental theory1. High Ability Studies, 15(2), 119–147. https://doi.org /10.1080/1359813042000314682

Gagné, Françoys. (2009) Building gifts into talents: Detailed overview of the DMGT 2.0. In: VanTassel-Baska, J., MacFarlane, B., & Stambaugh, T. (2009). Leading change in gifted education: the festschrift of Dr. Joyce VantasselBaska (First edition). Prufrock Press.

Geake, J. G., & Gross, M. U. M. (2008). Teachers’ Negative Affect Toward Academically Gifted Students: An Evolutionary Psychological Study. Gifted Child Quarterly, 52(3), 217–231. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986208319704

Geiger, T., & Pivovarova, M. (2018). The effects of working conditions on teacher retention. Teachers and Teaching, 24(6), 604-625.

Jung, J. Y. (2014). Predictors of attitudes to gifted programs/provisions: Evidence from preservice educators. Gifted Child Quarterly, 58(4), 247-258.

Jung, J. Y., Jackson, R. L., Townend, G., & McGregor, M. (2022). Equity in gifted education: The importance of definitions and a focus on underachieving gifted students. Gifted Child Quarterly, 66(2), 149-151.

Jung J.Y. & Worrell F.C. (2017) School psychological practice with gifted students. In: Thielking M., Terjesen M. (eds) Handbook of Australian School Psychology. Springer. https://doi-org.wwwproxy1.library.unsw.edu.au/10.1007/978 -3-319- 45166-4_29

Kronberg, L. (2018). Cultivating teachers to work with gifted students. In J.L. Jolly, & J.M. Jarvis (Eds.). Exploring gifted education: Australian and New Zealand perspectives (1st ed., pp.12-31). Routledge.

Lemon, N., & Garvis, S. (2016). Pre-service teacher self-efficacy in digital technology. Teachers and Teaching, 22(3), 387-408.

Navarro, S., Zervas, P., Gesa, R., & Sampson, D. (2016). Developing teachers' competences for designing inclusive learning experiences. Educational Technology and Society, 19(1), 17-27.

Nicpon, M. F., Allmon, A., Sieck, B., & Stinson, R. D. (2011). Empirical investigation of twice-exceptionality: where have we been and where are we going? Gifted Child Quarterly, 55(1), 3-17. https://doi:10.1177/0016986210382575

Norris, N. & Dixon, R. (2011). Twice exceptional gifted students with Asperger syndrome. Australasian Journal of Gifted Education, 20(2), 34-45

Rimm, S. B., Siegle, D., & Davis, G. A. (2018). Education of the gifted and talented. Pearson.

Ronksley-Pavia, M., & Neumann, M. M. (2020). Conceptualising gifted student (dis) engagement through the lens of learner (re) engagement. Education Sciences, 10(10), 274.

Rowan, L., & Townend, G. (2016). Early career teachers’ beliefs about their preparedness to teach: Implications for the professional development of teachers working with gifted and twice-exceptional students. Cogent Education, 3(1), 1242458.

Siegle, D., Rubenstein, L. D., & Mitchell, M. S. (2014). Honors students’ perceptions of their high school experiences: The influence of teachers on student motivation. Gifted child quarterly, 58(1), 35-50.

Townend, G., & Brown, R. (2016). Exploring a sociocultural approach to understanding academic self-concept in twice-exceptional students. International Journal of Educational Research, 80, 15-24.

Townend, G., & Pendergast, D. (2015). Student voice: What can we learn from twice-exceptional students about the teacher's role in enhancing or inhibiting academic self-concept. Australasian Journal of Gifted Education, 24(1), 37-51.

Wellisch, M. (2016). Gagne's DMGT and underachievers: The need for an alternative inclusive gifted model. Australasian Journal of Gifted Education, 25(1), 18-30.

Author:

Dr Geraldine Townend

NB: Please note that this article only represents the views of the author(s), and is not necessarily representative of the views of the Australian Association for the Education of the Gifted and Talented.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the AAEGT.

Share this resource

Resources